THE PETRILLO BAN

Trumpeter James C Petrillo had already been President of the Chicago Local 10 chapter of the American Federation of Musicians since 1922, when he was elected National President in 1940. Soon afterwards, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) wanted to re-negotiate the royalty rates their members were paid when their work was broadcast on radio. A stand-off led to ASCAP withdrawing their material, and only music recorded under the rival Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), was used for a year.

Trumpeter James C Petrillo had already been President of the Chicago Local 10 chapter of the American Federation of Musicians since 1922, when he was elected National President in 1940. Soon afterwards, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) wanted to re-negotiate the royalty rates their members were paid when their work was broadcast on radio. A stand-off led to ASCAP withdrawing their material, and only music recorded under the rival Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), was used for a year.  That dispute was resolved, but unlike the publishers, musicians didn’t get a raise, so Petrillo began to negotiate a better deal for his members with the record companies. He gave notice that they would not record any new music after July 1942, so the companies began to stockpile recordings of their most popular artists, so they would have something to sell when the strike took hold.

That dispute was resolved, but unlike the publishers, musicians didn’t get a raise, so Petrillo began to negotiate a better deal for his members with the record companies. He gave notice that they would not record any new music after July 1942, so the companies began to stockpile recordings of their most popular artists, so they would have something to sell when the strike took hold.

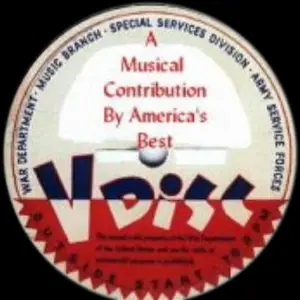

Late in 1943, Petrillo negotiated the recording of V-Discs for distribution to the Armed Forces, and soon some of the record companies ‘blinked’. Decca had been badly hit and they, and the new Capitol Records, both did a deal with the AFM. Other companies refused to budge, but a year later, after the intervention of President Roosevelt, industry leaders like RCA Victor and Columbia accepted the terms and the strike was over. The royalty issue came up again with TV networks in 1948, leading to another few months of strike, again with James Petrillo at the head of the AFM.

Late in 1943, Petrillo negotiated the recording of V-Discs for distribution to the Armed Forces, and soon some of the record companies ‘blinked’. Decca had been badly hit and they, and the new Capitol Records, both did a deal with the AFM. Other companies refused to budge, but a year later, after the intervention of President Roosevelt, industry leaders like RCA Victor and Columbia accepted the terms and the strike was over. The royalty issue came up again with TV networks in 1948, leading to another few months of strike, again with James Petrillo at the head of the AFM.

Musicians being conscripted into the Forces and War restrictions on petrol and tyres led to the end of touring Big Bands, and the new Jump-Blues and R&B that emerged in the late 40s were usually just a handful of players, and often a featured artist and his side-men.

Musicians being conscripted into the Forces and War restrictions on petrol and tyres led to the end of touring Big Bands, and the new Jump-Blues and R&B that emerged in the late 40s were usually just a handful of players, and often a featured artist and his side-men.

James Petrillo remained an official of the AMF in Chicago until 1962, and is memorialised in the Petrillo Bandshell in Grant Park, venue of many Chicago Blues Festivals and the annual Lollapalooza Festival.