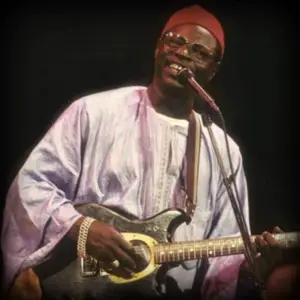

Ali Farka Toure

A Blues Legend from Mali?

If the east African nation of Mali seems like an unlikely place for the the rich tradition of the blues to flourish, it’s probably because you haven’t heard the music of Ali Farka Toure. One quick sample of Toure’s unmistakable sound will undoubtedly persuade the uninitiated.

If the east African nation of Mali seems like an unlikely place for the the rich tradition of the blues to flourish, it’s probably because you haven’t heard the music of Ali Farka Toure. One quick sample of Toure’s unmistakable sound will undoubtedly persuade the uninitiated.

Blues Beginnings

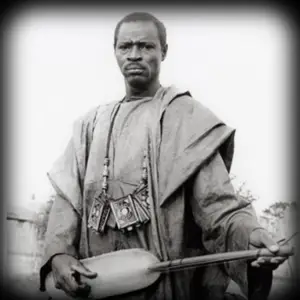

Although international renown didn’t come to the Malian guitarist until well past his fiftieth birthday, Toure’s journey, as is typical of blues greats, began at an early age. Born in a tiny village on the banks of the Niger river, he was his mother’s tenth son. But he earned the sad honor being the only one to survive beyond infancy. Somewhere in his youth, Toure earned the nickname “Farka,” for Donkey, the origin of which is rooted in the culture of his people. For starters, it was a custom for a child to be granted an odd nickname if he has had siblings who have passed away. Also, the moniker – far from being an insult – was selected because a donkey was admired for its stubbornness and tenacity.

Toure’s Donkey-like tenacity served him well through a lengthy apprenticeship in the blues. After meeting Keita Fodeba, the director of Guinea's National Ballet, the young Toure decided to take up the guitar. “I didn’t know his guitar but I liked it a lot. I felt I had as much music as him and that I could translate it.” By “Translate” he meant convert the music ideas from his native culture and filter them through the western six-string guitar.

In the decades that followed, he would slowly earn a new nickname: The African John Lee Hooker. But the journey from childhood “donkey” to legendary bluesman who’d earned a comparison to one of the genre’s all-time greats was riddled with challenges and struggles. And like any colossal blues man, he survived them all and wove his tribulations into the stories he’d share in his own time-tested voice.

The journey

The challenges came early. Moving from the traditional stringed instruments of his culture to the six-string guitar so popular in the West was no easy task – especially since it required going from the monochord. But mastery of this new instrument soon followed. And Toure wasn’t done yet. He would later add percussion, drums, symbols and bass drums to his repertoire.

The challenges came early. Moving from the traditional stringed instruments of his culture to the six-string guitar so popular in the West was no easy task – especially since it required going from the monochord. But mastery of this new instrument soon followed. And Toure wasn’t done yet. He would later add percussion, drums, symbols and bass drums to his repertoire.

His first official gig came in 1960 when his country’s new regime initiated a policy for the promotion of the arts. Asked to represent his district, Toure performed with and wrote for a 117-person troupe. Eight years later he was selected to represent the entire nation of Mali at an international festival of the arts in Bulgaria. But the trip was significant for reasons beyond national pride. It was Troure’s first step away from his native country. And it would also lead to the ownership of his first guitar after many years of toiling away on borrowed six-stringers.

An expansion of his musical horizons followed as he was introduced to the music of James Brown, Albert King, Jimmy Smith, Wilson Picket and most importantly John Lee Hooker.

Toure’s reaction, interestingly enough was not to find these blues sounds exotic – but rather to find them familiar. “This music has been taken from here.” In this case “here” meant Africa. Indeed he was stunned to hear the lyrics sung in English.

Even if you don’t know the words he’s singing on Savane, you’ll relate to every chord, every lick, and somehow, every word.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

The journey’s end

When Toure succumbed to bone cancer at In 2006, the world lost more than merely a gifted axman. It lost an intrepid explorer who bravely expanded the boundaries of the age-old genre. There was a time when combining traditional East African elements with the blues would have rendered the blues unrecognizable. But today, thanks to Ali Farka Toure, such varied sounds make perfect sense and are as much a part of the blues’ vocabulary as the harmonica or the call-and-response.

When Ali “Farka” Toure passed away, the world of music lost a truly unique voice.