THE DEATH OF BESSIE SMITH

It is 3a.m. in the middle of a sultry, moonless Saturday night in late September 1937. A Packard car is cruising south down Highway 61 in Coahoma County, Mississippi.

It is 3a.m. in the middle of a sultry, moonless Saturday night in late September 1937. A Packard car is cruising south down Highway 61 in Coahoma County, Mississippi.

At the wheel is Richard Morgan, a well-known Chicago club owner and ex-bootlegger: the passenger is his girlfriend Bessie Smith. She is still a star of the Blues scene and, although she has not recorded in a couple of years, her public appearances and fearsome reputation for hard living have ensured her lasting fame. Drowsy from the long journey, she dangles her arm out of the window of the car to take advantage of the cool night air. Up ahead a truck driver has pulled off the road to check a tyre and, as he starts out again on the two lane concrete road, the Packard comes up behind him.

The weary Morgan misjudges the distance to the tail-lights and slams on the brakes. The car swerves left to avoid the rear of the truck, but it side-swipes the tailgate, almost severing Bessie’s arm at the elbow and causing severe injuries to the right side of her torso.

A few minutes later a car approached from the north containing two men, Henry Broughton and Dr. Hugh Smith. They were setting off on a dawn fishing trip when they came upon the scene. Morgan was sober but distressed and seemed physically unhurt, but Bessie was unconscious on the roadside and bleeding from her arm. There was no sign of the truck. The Doctor gave first-aid to Bessie but she was obviously going to need hospital treatment. Broughton went to a nearby house to summon help. When he returned, there was some talk of transferring Bessie to Dr. Smith’s car, but she weighed 200lb and was suffering internal injuries. She was drifting in and out of consciousness, suffering from shock and having breathing difficulties. Soon another car approached from the north, this time containing a drunk white couple. Their car slammed hard into the back of Dr. Smith’s car which then shunted into the back of the Packard. Dr. Smith found that the driver had rib injuries but was not badly hurt, and his passenger was unhurt but hysterical.

As Dr. Smith examined the couple, an ambulance arrived along with several local officers of The Law. They put Bessie in the ambulance and Morgan accompanied her to hospital in Clarksdale. As this was happening, a second ambulance arrived: apparently the first one had been sent by the truck driver when he stopped in Clarksdale and the second one, called by Henry Broughton, took care of the white couple.

At this point, the story becomes controversial. Bessie’s family claim that Richard Morgan told them that they went to a white hospital and were turned away because Bessie was black. This was the basis of a story by John Hammond Sr. published in the October 1937 issue of Downbeat Magazine. After noting that Bessie’s arm was almost severed in a serious crash, and that a second collision delayed her arrival at the hospital, which he said was in Memphis, Hammond goes on; “When finally she did arrive at the hospital, she was refused treatment because of her colour and bled to death”. This caused an understandably heated debate, and the incident became a ’cause celebre’ for the forces advocating social change in the South at that time.

Dr. Smith gave a detailed interview to Bessie’s adopted son Jack Gee Jnr. in 1938, and his later conversation with Chris Albertson is available at http:/stomp-off.blogspot.com/2010/10/death-of-bessie-smith.html

Dr. Smith gave a detailed interview to Bessie’s adopted son Jack Gee Jnr. in 1938, and his later conversation with Chris Albertson is available at http:/stomp-off.blogspot.com/2010/10/death-of-bessie-smith.html

During that interview the Doctor recalled, “Down in the deep South cotton country, no coloured ambulance driver, or white driver, would even have thought of putting a coloured person off at a hospital for white folks. In Clarksdale in 1937, there were two hospitals, one white and one coloured, and they weren’t half a mile apart. I suspect the driver drove just as straight as he could to the coloured hospital.” In 1957 a black man, Willie George Miller, claimed he was that ambulance driver. He remembered taking Bessie directly to the coloured hospital, the G.T. Thomas Hospital on Sunflower Avenue, Clarksdale, but thought she may have been dead on arrival. This could not be true as surgeons later amputated her arm, but were unable to save her.

Bessie’s Death Certificate shows she died in Ward 1 of the G.T. Thomas Hospital at 11.30 am. on 26th September 1937. Cause of death is listed as; Shock, Internal injuries, Multiple fractures of right arm. It notes that her arm had been amputated at the hospital.

Downbeat Magazine later ran a lead article correcting Hammond’s assertions and noting the role of Dr. Smith, but this seems not to have had the impact of the original story. Richard Morgan died in 1943, and was never interviewed by Police or reporters. In the 1970s, following Chris Albertson’s excellent biography of Bessie, John Hammond admitted that his article was based on hearsay and rumours that circulated in Memphis in the days following Bessie’s death, and that he had made no attempt to contact the witnesses or the hospitals. Yet this fiction has entered the mythology of the Blues. Hammond had a liberal agenda, and the segregated South discriminated viciously against it’s Black citizens, but his version of the story amounts to reckless journalism, if not deliberate deception.

The myth was amplified in 1959 when Edward Albee wrote a one-act play titled ‘The Death of Bessie Smith’, which is set in the ‘White’ hospital where she was supposed to have been taken. The play takes the form of dialogues between two black men and an off-stage presence of ‘Bessie’ and with the white hospital staff, among others. The piece was immediately controversial in the era when the Civil Rights movement was gaining support to repeal the ‘Jim Crow’ laws in the Southern States, and has been performed many times over the decades.

Hammond and Albee’s motives were undoubtedly affected by the politics of the day, but in the light of evidence that has emerged, their claim that Bessie was ‘turned away on account of her colour’ seems extremely unlikely. As we look back over three-quarters of a century we can see that Bessie’s death was a tragedy and a huge loss to African-American culture, but it had very little to do with racism.

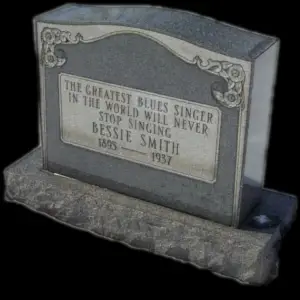

Bessie Smith was The Empress of the Blues and the First Black Superstar. She should be remembered for that above anything else.