‘FROM SPIRITUALS to SWING’ – JOHN HAMMOND Sr.

In 1938, the 'Spirituals to Swing' Concert at Carnegie Hall in New York celebrated the contribution that African-American musicians had made to popular American culture over the previous decades. The Blues had grown up in the South as a folk music which documented the hard life of sharecropping field hands. It remained in the Delta, where it was the origin of the music developed by WC Handy and Ma Rainey, but when refugees from the brutality of rural life migrated to New Orleans at the end of the 19th Century, they took their music to America's 'melting pot'. The city was already full of French, Spanish and Caribbean influences, and the Afro-American religious tradition of Gospel 'spirituals'.

In 1938, the 'Spirituals to Swing' Concert at Carnegie Hall in New York celebrated the contribution that African-American musicians had made to popular American culture over the previous decades. The Blues had grown up in the South as a folk music which documented the hard life of sharecropping field hands. It remained in the Delta, where it was the origin of the music developed by WC Handy and Ma Rainey, but when refugees from the brutality of rural life migrated to New Orleans at the end of the 19th Century, they took their music to America's 'melting pot'. The city was already full of French, Spanish and Caribbean influences, and the Afro-American religious tradition of Gospel 'spirituals'.

This combined with the local taste for brass marching bands, and the result was a heady mixture of improvised music that became known as Jazz, which flourished in the bars and 'sporting houses' of Storyville. Based on a Blues tone that is just as fundamental to the music as 'scales' are to European music, Buddy Bolden's cornet, Jelly Roll Morton's piano and the clarinet of Sidney Bechet inspired generations of musicians who spread the music during the 'Great Migration' to Chicago, New York and other Northern cities. Black musicians could not get their music recorded because of racist assumptions about record buyers, so early Jazz was only recorded by white musicians copying the originators. By the early 20s, the 'race music' market opened up recording to 'Blues Divas', women who sang the Blues and sold mainly to a black audience. Black men singing about what might be seen as the injustice of their lives was politically difficult, but their records began to appear some years later in field recordings of country Blues, along with the work of Jazz men like King Oliver and Louis Armstrong. The 30s was an era when 'black' and 'white' music had different record labels, radio stations and sales charts, regardless of the 'integration' that had taken place to a greater or lesser extent outside the segregated South. At concerts, audiences were separated on racial lines in most parts of the country and in the recording industry, many great songs by black artists were 'covered' by their white counterparts, making huge amounts of money, often without giving credit. A rich New Yorker was about to do something to redress the balance.

JOHN HAMMOND Sr.

John Henry Hammond II was born in New York in 1910 into an extremely wealthy family: he was the great-grandson of W H Vanderbilt. His first encounter with music came in 1922, when he was in London with his family, where he saw Sidney Bechet, the New Orleans clarinettist, and this led him to trawl the record stores of Harlem in search of more swinging Jazz. When he left school, John worked for a newspaper in Portland Maine before attending Yale, where he acted as correspondent for the British weekly Melody Maker. He dropped out in 1931 and moved to Greenwich Village where he hired recording studios and organised concerts for his favourite Jazz artists. He continued to write about music and society, seeing it as a template for racial integration, and he paid a radio station to allow him to play his choice of music, using records by both black and white artists. John continued to work as a producer, recording Fletcher Henderson and Benny Carter, and when Benny Goodman, a Jewish clarinettist from Chicago, bought Fletcher's 'book', Jazz began to demolish the race barrier, especially when John helped to recruit black players like Charlie Christian, Teddy Wilson and Lionel Hampton into Goodman's band. John took the young Billie Holiday from a Harlem club to world fame, and when he heard Count Basie on a Kansas City radio station, he called him to New York and launched his massive career. John was involved in the controvery surrounding the death of Bessie Smith, when an article he wrote for Downbeat Magazine wrongly stated that she died because she had been refused treatment at a 'white' hospital in Memphis.

FROM SPIRITUALS to SWING

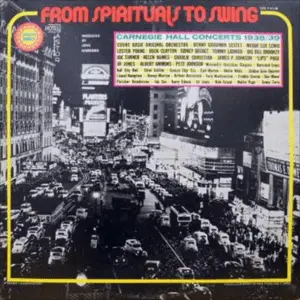

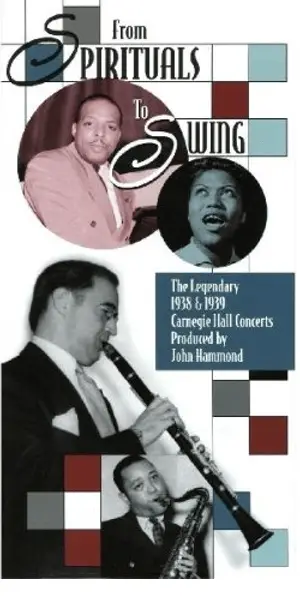

In 1938, John organised a concert of 'black' music which he called 'From Spirituals to Swing' designed to spotlight the huge contribution 'Race Music' had made to popular American culture. Gospel, Blues and Jazz players assembled on December 23rd in front of an integrated audience at Carnegie Hall for this seminal event. The bill included Count Basie's Orchestra, featuring 'Hot Lips' Page and Jimmy Rushing; boogie-woogie pianists Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis, along with another boogie-man Pete Johnson, who accompanied Big Joe Turner; Big Bill Broonzy played some rocking Blues, apparently in place of Robert Johnson, who had died a few months previously; Sonny Terry played Blues harp; Sister Rosetta Tharpe and The Golden Gate Quartet represented the Spiritual element, and The Kansas City Six played more Jazz. The show was a huge success, and the pianists, Albert, Meade and Pete, started a 'Boogie-woogie craze' that spread a new dance all over the country. All the artists saw their record sales increase, and although the concert was recorded, it was not released on disc until 1959.

In 1938, John organised a concert of 'black' music which he called 'From Spirituals to Swing' designed to spotlight the huge contribution 'Race Music' had made to popular American culture. Gospel, Blues and Jazz players assembled on December 23rd in front of an integrated audience at Carnegie Hall for this seminal event. The bill included Count Basie's Orchestra, featuring 'Hot Lips' Page and Jimmy Rushing; boogie-woogie pianists Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis, along with another boogie-man Pete Johnson, who accompanied Big Joe Turner; Big Bill Broonzy played some rocking Blues, apparently in place of Robert Johnson, who had died a few months previously; Sonny Terry played Blues harp; Sister Rosetta Tharpe and The Golden Gate Quartet represented the Spiritual element, and The Kansas City Six played more Jazz. The show was a huge success, and the pianists, Albert, Meade and Pete, started a 'Boogie-woogie craze' that spread a new dance all over the country. All the artists saw their record sales increase, and although the concert was recorded, it was not released on disc until 1959.

The event was repeated on Christmas Eve the following year, again with Count Basie, fronted by Helen Humes' singing this time; Benny Goodman's Sextet featuring Charlie Christian, Fletcher Henderson and Lionel Hampton; James P Johnson played his 'stride' piano; Ida Cox performed some of the songs she made famous as one of the 'Blues Divas' of the 20s; Big Bill, Albert Ammons and Sonny Terry came back to play the Blues again, in another famous night of music. The spectre of War in Europe stopped this becoming an annual event. The main impact of the shows on American society was to emphasise that music had no colour, and that to accept the music of African-Americans was to acknowledge a common humanity.

POST-WAR

After Military service in WWII, John resumed his career as an executive with Columbia, where he signed Pete Seeger and discovered Aretha Franklin. He signed Bob Dylan to the label and produced his early recordings, then arranged for the release of the complete works of Robert Johnson as 'The King of the Delta Blues', but he did not seem to help much with the career of his son, John Hammond Jr. who was making a name for himself as a Delta Blues preservationist singer and guitarist. John Sr, as he was now known, went on to sign Leonard Cohen and Bruce Springsteen to the label, and is credited as Executive Producer of Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'Texas Flood', even though he had been retired for several years at that piont. John Sr's health was deteriorating, and he passed away in 1987, reportedly listening to the music of Billie Holiday.