CHARLEY PATTON

Charley Patton liked to put on a show. He could make his guitar sound loud and rough, playing it between his legs and behind his back. He leapt about the stage clowning around, sometimes beating the back of his guitar like a drum.

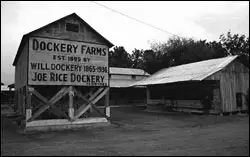

His raw earthy voice reflected his hard living, his heavy drinking and smoking, his perpetual fighting and his general disregard for the quiet life. Charley was a cocky and belligerent man who was thrown off the Dockery Plantation three times, married eight (!) times and served at least one spell in jail. His music displayed his life, and his powerful influence on his contemporaries and his legacy of recordings were arguably the most important factors in making the Delta sound the driving force behind the Blues.

Patton’s family moved to the Will Dockery Plantation outside Clarksdale Mississippi in about 1900 when Charley would have been nine years old. They were sharecroppers raising cotton, giving part of the crop to their landlord. It was very hard work, back-breaking field labor under the unforgiving sun, but the workers cut loose at the weekends with parties and drinking, making time for Church on Sunday! In the barrelhouses and juke-joints around the area, Charley heard another Dockery farmer Henry Sloan, a pioneer of the passionate Delta Blues that mixed field hollers with percussive guitar riffs. Many other musicians passed through the Delta plantations, picking up and spreading tunes and songs, but Charley followed Henry around and eventually got good enough to play with him.

Son House said that “Charley hated work like God hates Sin!”, but he had quickly become a talented performer, and spent most of his time bumming round the Delta with another friend, Willie Brown. In 1916 Charley played with WC Handy, but turned down a job in his band. His songs went beyond the usual laments of poverty and lost love. ‘Pony Blues’ deals with social mobility, ‘High Water Everywhere’ is about the flood of ’27, and he sang about prison, drug use (Spoonful Blues) even his own mortality in ‘Oh, Death’. His powerful playing, incisive lyrics and engaging showmanship made him a role model for the young players around him like Tommy Johnson, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf.

The original recording of ‘Pony Blues’;

Patton was thirty-eight when he cut his first record for Paramount in June 1929, and at that first session Charley also recorded ‘The Prayer of Death’ under the name Deacon JJ Hadley, to exploit the market for ‘guitar evangelists’. ‘Pony Blues’, ‘High Water Everywhere’ and five other records sold so well, Charley went back in October to make more recordings accompanied by the fiddler Henry ‘Son’ Sims. Later in 1930, Son House and Willie Brown joined Charley for further a extensive period of recording at Paramount’s headquarters in Wisconsin, which probably yielded his finest work, but the economic depression killed record sales for several years.

By 1934 Charley had served some jail time and had suffered a throat wound in a fight, but in January that year he and his new wife Bertha Lee were invited to New York by ARC. Their recordings show his voice was failing and most of the material was not new. A version of, ‘Oh, Death’ was prophetic; in April he died of heart failure in Indianiola, Mississippi.

In so many ways he earned his description as a Pioneer of the Blues.