HOKUM BLUES

‘Hokum’ is a term applied to a kind of raunchy Blues song that was popular in the late 20s and early 30s in America. The lyrics on some of those records that sold in their hundreds of thousands were quite explicit in their references to sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality and other things which would scare your maiden Aunt. This ‘Hokum’ craze grew up in the steamy atmosphere of the ‘Prohibition’ era, when drinking alcohol criminalised large parts of the population, and the permissive aura around anyone pursuing an interest in nightlife extended to sexual activity, gambling and other ‘immoral’ and subversive activities. It wasn’t remembered as ‘The Roaring Twenties’ for nothing!

‘Hokum’ is a term applied to a kind of raunchy Blues song that was popular in the late 20s and early 30s in America. The lyrics on some of those records that sold in their hundreds of thousands were quite explicit in their references to sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality and other things which would scare your maiden Aunt. This ‘Hokum’ craze grew up in the steamy atmosphere of the ‘Prohibition’ era, when drinking alcohol criminalised large parts of the population, and the permissive aura around anyone pursuing an interest in nightlife extended to sexual activity, gambling and other ‘immoral’ and subversive activities. It wasn’t remembered as ‘The Roaring Twenties’ for nothing!

Signifying

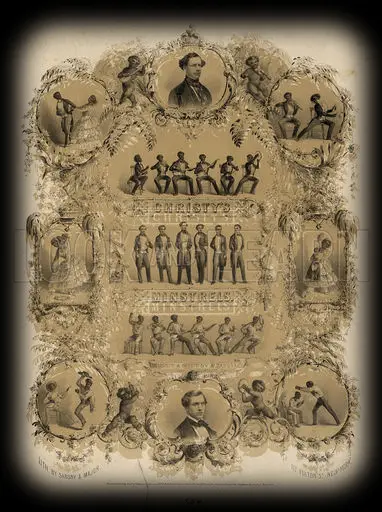

Minstrel Show Origins

From the 1830s onwards, Minstrel Shows were the popular music of the age in America. TD Rice published ‘Jump, Jim Crow’ and Stephen Foster of The Christy Minstrels put out ‘Oh Susannah’ and ‘Camptown Races’ as white musicians donned ‘blackface’ to mock and parody African-Americans. Other groups like the Irish and Chinese were lampooned too, but aside from race, the other main subject of popular songs was sex. Burlesque theatres specialised in presenting semi-nude showgirls and scandalous songs as their main attraction, but lyrics could not be too explicit for fear of the authorities closing the premises. Many bawdy songs were adapted from English, Irish and Scottish folk traditions in the late 19th Century, and were played out in travelling shows and vaudeville venues. As such they were part of the repertoire of work songs, Gospel tunes, ballads and lullabies that were all part of the ‘common stock’ of popular music that early Blues singers adapted to their new musical form.

From the 1830s onwards, Minstrel Shows were the popular music of the age in America. TD Rice published ‘Jump, Jim Crow’ and Stephen Foster of The Christy Minstrels put out ‘Oh Susannah’ and ‘Camptown Races’ as white musicians donned ‘blackface’ to mock and parody African-Americans. Other groups like the Irish and Chinese were lampooned too, but aside from race, the other main subject of popular songs was sex. Burlesque theatres specialised in presenting semi-nude showgirls and scandalous songs as their main attraction, but lyrics could not be too explicit for fear of the authorities closing the premises. Many bawdy songs were adapted from English, Irish and Scottish folk traditions in the late 19th Century, and were played out in travelling shows and vaudeville venues. As such they were part of the repertoire of work songs, Gospel tunes, ballads and lullabies that were all part of the ‘common stock’ of popular music that early Blues singers adapted to their new musical form.

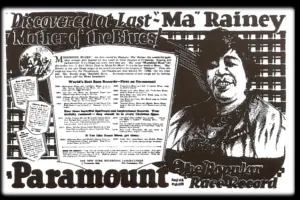

‘Race Records’

There were almost no recordings of African-American musicians before Mamie Smith‘s 1920 song ‘Crazy Blues’ opened up the market for ‘race music’ and kick-started the careers of Blues Divas like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. Jodie ‘Butterbeans’ Edwards and Susie Hawthorn were vaudeville performers whose stage act was that of a wisecracking husband and a frustrated wife, and their first record ‘He Likes It Slow’ in 1926 featured a young Louis Armstrong. The follow-up ‘I Want a Hot-Dog in my Roll’ was typical of their output and they led the way for other ‘rude’ acts and, although they were not well known outside the African-American community, the couple were still performing into the 60s. In the late 20s, Jug-Bands like Gus Cannon‘s Jug Stompers and Will Shade‘s Memphis Jug Band used a lot of suggestive material. The bands tended to be made up of black musicians, playing to both black and white audiences, as their humour crossed the ‘race line’, but the politics of the day meant those audiences could not be integrated. The Mississippi Sheiks were another Memphis institution, and their guitarist Arminter Chapman had a big solo career in Hokum Blues using the name Bo Carter, recording songs like ‘Banana in Your Fruit Basket’ and ‘Warm My Wiener’. In Chicago in 1928, Tampa Red and Georgia Tom had a huge hit with ‘Tight Like That’ and at that point the ‘hokum’ craze really caught on. They formed The Hokum Boys with a tiny transvestite called Frankie ‘Half-pint’ Jaxon, and many more salacious songs followed, including a suggestive version of Leroy Carr‘s hit ‘How Long, How Long’. Many established stars took up the trend, like Ma Rainey’s ‘Black Bottom’ and Bessie Smith’s ‘Bumpy Ride’.

There were almost no recordings of African-American musicians before Mamie Smith‘s 1920 song ‘Crazy Blues’ opened up the market for ‘race music’ and kick-started the careers of Blues Divas like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. Jodie ‘Butterbeans’ Edwards and Susie Hawthorn were vaudeville performers whose stage act was that of a wisecracking husband and a frustrated wife, and their first record ‘He Likes It Slow’ in 1926 featured a young Louis Armstrong. The follow-up ‘I Want a Hot-Dog in my Roll’ was typical of their output and they led the way for other ‘rude’ acts and, although they were not well known outside the African-American community, the couple were still performing into the 60s. In the late 20s, Jug-Bands like Gus Cannon‘s Jug Stompers and Will Shade‘s Memphis Jug Band used a lot of suggestive material. The bands tended to be made up of black musicians, playing to both black and white audiences, as their humour crossed the ‘race line’, but the politics of the day meant those audiences could not be integrated. The Mississippi Sheiks were another Memphis institution, and their guitarist Arminter Chapman had a big solo career in Hokum Blues using the name Bo Carter, recording songs like ‘Banana in Your Fruit Basket’ and ‘Warm My Wiener’. In Chicago in 1928, Tampa Red and Georgia Tom had a huge hit with ‘Tight Like That’ and at that point the ‘hokum’ craze really caught on. They formed The Hokum Boys with a tiny transvestite called Frankie ‘Half-pint’ Jaxon, and many more salacious songs followed, including a suggestive version of Leroy Carr‘s hit ‘How Long, How Long’. Many established stars took up the trend, like Ma Rainey’s ‘Black Bottom’ and Bessie Smith’s ‘Bumpy Ride’.

Hard Core

“I got nipples on my titties, big as my thumb,

Got something ‘tween my legs’ll make a dead man come”.

Parental Guidance

Compilations of Lucille’s Greatest Hits carry a ‘Parental Guidance’ sticker today following a ‘moral panic’ over lyrics in the mid-80s, but the content of songs has always been a controversial subject. From raunchy Victorian vaudeville songs to ‘hokum Blues’, and from Rock’n’Roll ‘juvenile delinquent’ anthems to modern Rap videos, lyrics are open to interpretation, as musicians exploit covert meanings in their songs. It is a ‘problem’ that defies solution, as the use of slang and subculture references will always run ahead of any attempt at legislation, and the complainants tend to end up looking foolish. Any attempt to ban a song tends to assure it wider exposure because of the publicity a ban generates. When Hank Ballard‘s song ‘Work with Me Annie’ was banned from radio airplay in 1954, it sailed to the top of the charts, as did the follow-ups ‘Annie Had a Baby’ and ‘Annie’s Aunt Fannie’. Perhaps it is best regarded as a matter of taste: “A tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Compilations of Lucille’s Greatest Hits carry a ‘Parental Guidance’ sticker today following a ‘moral panic’ over lyrics in the mid-80s, but the content of songs has always been a controversial subject. From raunchy Victorian vaudeville songs to ‘hokum Blues’, and from Rock’n’Roll ‘juvenile delinquent’ anthems to modern Rap videos, lyrics are open to interpretation, as musicians exploit covert meanings in their songs. It is a ‘problem’ that defies solution, as the use of slang and subculture references will always run ahead of any attempt at legislation, and the complainants tend to end up looking foolish. Any attempt to ban a song tends to assure it wider exposure because of the publicity a ban generates. When Hank Ballard‘s song ‘Work with Me Annie’ was banned from radio airplay in 1954, it sailed to the top of the charts, as did the follow-ups ‘Annie Had a Baby’ and ‘Annie’s Aunt Fannie’. Perhaps it is best regarded as a matter of taste: “A tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”