RACE MUSIC

Blues, jazz, R&B, funk, rap and hip-hop are all examples of the Black music that helped to shape our culture today, but this music grew and developed in a historical context. From the beginning of the 20th Century, African music’s rhythms and tradition of improvisation have dominated popular music, but in the early days this music was only heard in the communities where it was made. Recording, radio and then film and video have made Black music available to the world, but when these methods of distribution were getting started, the music was directed specifically to the African-American population, and it was known as ‘Race Music’.

Blues, jazz, R&B, funk, rap and hip-hop are all examples of the Black music that helped to shape our culture today, but this music grew and developed in a historical context. From the beginning of the 20th Century, African music’s rhythms and tradition of improvisation have dominated popular music, but in the early days this music was only heard in the communities where it was made. Recording, radio and then film and video have made Black music available to the world, but when these methods of distribution were getting started, the music was directed specifically to the African-American population, and it was known as ‘Race Music’.

‘Race Music’ dominated by Blues Divas.

In January 1916 The Chicago Defender, a national weekly African-American newspaper with a readership of near a million, asked why there were no commercial recordings by Black artists. It also posed the question, “How many Victrolas are owned by members of our race?” The question was never answered, but when Perry Bradford persuaded Okeh Records to record Mamie Smith‘s version of his composition ‘Crazy Blues’ in November 1920, they were astounded to find that in the first month after release, 75,000 people would spend $1 to buy a copy. The sheer economic impact of that record meant that ‘Race Music’ had arrived. Other companies were quick to cotton on to the commercial possibilities, and about 100 records by African-American female singers were issued over the next two years, as each label looked to sign their own ‘Blues Diva’. The most popular was Lucille Hegamin, who recorded nine songs for the Arto company in 1921/22, and these were leased by a dozen different labels around the country. The major record companies did not have a feel for African-American musical tastes, and they had little contact with talented Blues singers beyond leasing a few master tapes and signing up the occasional cabaret artist they found performing in their citys’ speakeasies. In 1921, WC Handy‘s lyricist Harry Pace left their joint publishing company to set up Black Swan Records, with a mission to find and develop the best singers and musicians among the African-American population, which was approaching eleven million at that time. Fletcher Henderson was engaged as musical director and Pace sought to widen the label’s appeal by recording vocal quartets, ‘glee-clubs’ and vaudeville acts, but the real sales came from Blues Divas like Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter.

Early Race Music and Blues Men.

There were no recordings of male Blues singers at this time. African-American men had been heard on record from the early days, with the Victor label advertising The Dinwiddie Coloured Quartet singing “genuine Jubilee and Camp Meeting Shouts as only negroes can sing them” in 1903. Vaudeville commedian Bert Williams recorded his song ‘Nobody’ on 1906, and further tracks in his later career. Scott Joplin did not make any records, but Wilbur Sweatman cut a version of his ‘Maple Street Rag’ among others, but these were rare events. Jazz was becoming popular in urban America, and although the originators and innovators of this music were largely African-American, the first Jazz records were made by The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, who were white musicians. Their hits ‘Tiger Rag’ and ‘Darktown Strutters Ball’ gave the music a big commercial lift, but the bands that played this popular new music tended to be segregated because, in general, venues would not book integrated groups. Almost all the recorded jazz was by white players and even the hugely popular ‘King’ Oliver did not record until 1923. African-American Bluesmen were not welcome in the studio either, perhaps because their songs of oppression and need were considered to be too hot to handle politically at a time of the ‘Black Diaspora’, with the rise of the Klan in the south and race riots in Northern cities. The growing demand for Blues music would eventually breach this barrier, but in the early 20s, nobody was ready to make that breakthrough.

There were no recordings of male Blues singers at this time. African-American men had been heard on record from the early days, with the Victor label advertising The Dinwiddie Coloured Quartet singing “genuine Jubilee and Camp Meeting Shouts as only negroes can sing them” in 1903. Vaudeville commedian Bert Williams recorded his song ‘Nobody’ on 1906, and further tracks in his later career. Scott Joplin did not make any records, but Wilbur Sweatman cut a version of his ‘Maple Street Rag’ among others, but these were rare events. Jazz was becoming popular in urban America, and although the originators and innovators of this music were largely African-American, the first Jazz records were made by The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, who were white musicians. Their hits ‘Tiger Rag’ and ‘Darktown Strutters Ball’ gave the music a big commercial lift, but the bands that played this popular new music tended to be segregated because, in general, venues would not book integrated groups. Almost all the recorded jazz was by white players and even the hugely popular ‘King’ Oliver did not record until 1923. African-American Bluesmen were not welcome in the studio either, perhaps because their songs of oppression and need were considered to be too hot to handle politically at a time of the ‘Black Diaspora’, with the rise of the Klan in the south and race riots in Northern cities. The growing demand for Blues music would eventually breach this barrier, but in the early 20s, nobody was ready to make that breakthrough.

Record labels.

In 1922, Black Swan bought the Olympic pressing plant, increased its releases to 10 a month and brought down the price of records to 75 cents. Over in LA, the Sunshine label put out three Blues records by Roberta Dudley and Ruth Lee, backed by Kid Ory‘s Jazz Band, but they never made it outside California and there was no more Blues music recorded on the West Coast for nearly 20 years. The Wisconsin Chair Company had begun producing phonographs as part of their furniture range, and they formed a subsidiary to produce records. At first they leased masters from Paramount in New York, but in 1922 set up their own studio to record music for their ‘Popular’ label, specialising in Race Records. The Okeh label remained the market leader with Mamie Smith’s records, as well as those of Daisy Martin, Josephine Carter and Lizzie Miles.

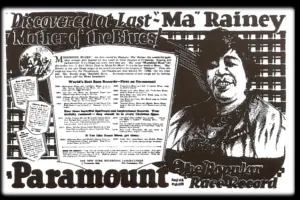

By early 1923, The Defender carried advertisements for Okeh’s ‘Original Race Records’ and Paramount’s ‘Popular Race Records’, and a genuine industry was emerging. Later that year Columbia, who were keen to get into this new market, signed Bessie Smith and her first records sold in unprecedented numbers. At Paramount, J Mayo ‘Ink’ Williams took over the Race Artist Series and signed Ma Rainey, whose popularity as a live performer had been ignored by the record companies.

Field recordings bring in African-American men.

It was obvious that there were not enough girl singers to satisfy the demand of the growing urban African-American population, and talent scouts began to travel the Southern countryside, seeking out new and interesting players. Some sent recording engineers and equipment South to set up impromptu studios and, in 1923, Okeh recorded Lucille Bogan‘s ‘Pawn Shop Blues’ in Atlanta GA. They also recorded Ed Andrews’ ‘Barrel-house Blues’ in Atlanta in 1924, but the first Blues hit record by a man came later that year with ‘Papa’s Lawdy, Lawdy Blues’, by Papa Charlie Jackson. This banjo playing minstrel had eight more records out in the following year and was one of Paramount’s top artists over the next five years. Paramount were also responsible for Blind Lemon Jefferson‘s success after hearing some tracks he had cut in a Dallas music store. He had eight records issued in 1926, when Paramount also signed up Blind Blake. The success of Jefferson and Blake opened the eyes of other companies to the possibilities of ‘country Blues’. Paramount took over Black Swan Records and the Okeh label was sold to Columbia in 1926, and these two were the biggest distributors of Race records. The Vocalion and Brunswick labels were jointly owned by a single company, and RCA Victor and the small Gennett label made up the five main companies that competed in the developing Race market.

Sermons and Sacred Music.

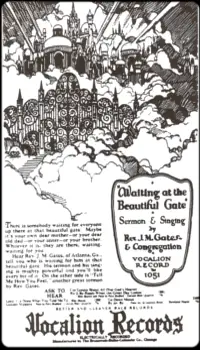

In 1926, astonishingly high record sales were achieved by Rev. JM Gates as he belted out his hell-fire sermons along with a few members of the congregation to ‘Amen!’ and join in the hymns. His ‘Dying Gambler’ and ‘Death’s Black Train is Coming’ sold well in African-American communities all over the country and, refusing exclusive contracts, he recorded for all the Race labels. Rev. JC Burnett, Rev. WM Mosley and Rev. Mose Dolittle all had big-selling sermons on Race labels, and this ‘sermon boom’ was just as important as Blues music in establishing the economic viability of the industry. Some crossover of style was apparent with the ‘guitar evangelists’, like Rev. Edward Clayborn and Blind Joe Taggart who used a country Blues format to ‘spread the word’, and both had big-selling records in 1927. Columbia sent their field-units South in 1927 and they picked up music from Peg-Leg Howell and Barbecue Bob in Atlanta before moving on to Dallas where they recorded the ‘guitar evangelist’ Blind Willie Johnson. The outstanding guitarist Lonnie Johnson had been recording regularly for Okeh, and he accompanied their field-unit as it recorded Mississippi John Hurt in Memphis and Texas Alexander when they called at Dallas. Victor concentrated on the area around Memphis, and were rewarded with a fine crop of Delta Blues players like Tommy Johnson, Ishmon Bracey and Frank Stokes as well as The Memphis Jug Band and Gus Cannon‘s Jug Stompers. Other Blues legends to make their mark in 1927 included pianist Cow Cow Davenport and Cryin’ Sam Collins, as country guitar pickers, barrel-house pianists and Blues Divas found their records on sale next to Gospel choirs and proclaiming Ministers.

In 1926, astonishingly high record sales were achieved by Rev. JM Gates as he belted out his hell-fire sermons along with a few members of the congregation to ‘Amen!’ and join in the hymns. His ‘Dying Gambler’ and ‘Death’s Black Train is Coming’ sold well in African-American communities all over the country and, refusing exclusive contracts, he recorded for all the Race labels. Rev. JC Burnett, Rev. WM Mosley and Rev. Mose Dolittle all had big-selling sermons on Race labels, and this ‘sermon boom’ was just as important as Blues music in establishing the economic viability of the industry. Some crossover of style was apparent with the ‘guitar evangelists’, like Rev. Edward Clayborn and Blind Joe Taggart who used a country Blues format to ‘spread the word’, and both had big-selling records in 1927. Columbia sent their field-units South in 1927 and they picked up music from Peg-Leg Howell and Barbecue Bob in Atlanta before moving on to Dallas where they recorded the ‘guitar evangelist’ Blind Willie Johnson. The outstanding guitarist Lonnie Johnson had been recording regularly for Okeh, and he accompanied their field-unit as it recorded Mississippi John Hurt in Memphis and Texas Alexander when they called at Dallas. Victor concentrated on the area around Memphis, and were rewarded with a fine crop of Delta Blues players like Tommy Johnson, Ishmon Bracey and Frank Stokes as well as The Memphis Jug Band and Gus Cannon‘s Jug Stompers. Other Blues legends to make their mark in 1927 included pianist Cow Cow Davenport and Cryin’ Sam Collins, as country guitar pickers, barrel-house pianists and Blues Divas found their records on sale next to Gospel choirs and proclaiming Ministers.

Race Music sales enter a ‘Golden Age’.

The period from 1926-29 was something of a ‘Golden Age’ for the Blues. Field recordings became less important to the major Race labels as they set up permanent studios such as Paramount’s facility at Grafton WS, with electronic recording and experienced engineers. Charley Patton, Son House, Skip James and a host of others travelled North to recording sessions that yielded some classic Blues songs.

In Indianapolis, Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell recorded ‘How Long, How Long Blues’ which began a fashion for guitar/piano duets, and when the duo Tampa Red and ‘Georgia Tom’ Dorsey released ‘Tight Like That’ in December 1928 in Chicago, it started a craze for suggestive ‘Hokum’ Blues. This chimed well with the culture of decadence and speakeasies in the cities and at ‘juke-joints’ in the countryside. In Memphis, Jug-Bands were recording good-time party music for a population with disposable income, and the Race Music market seemed to have an optimistic future. The popularity of Blues music; the ‘sermon boom’ and it’s associated gospel choirs; jug bands and ‘guitar evangelists’; and also the increasing crossover into white markets from established Blues stars like Bessie Smith, were all signs of a confident industry. Bessie herself appeared on film in one of the first ‘talkies’, and movements like the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ meant that African-American culture was raising its profile in the nation.

In answer to The Defender’s question of 1916, “How many Victrolas are owned by our race?” it has been estimated that, by the late 20s, in the African-American population, one home in eight in urban areas and one in twelve in rural areas owned a Victrola. This gave a huge potential market for Race Music. Then in November 1929 came the Wall Street Crash, and everything was about to change.