T-BONE WALKER

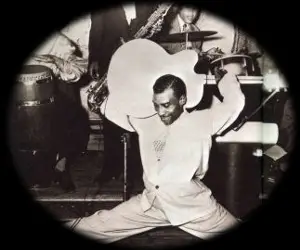

T-Bone Walker has a good claim to be the first guitar hero. He put out the first electric Blues record and his eloquent phrasing and masterful command of this new instrument made him the prototype for millions that followed, even if they had never heard of him! He was a powerful singer and entertainer too: his full-bodied and expressive voice was equally at home in a small band or in front of a full orchestra. T-Bone’s supremely confident stage prescence harked back to the great Charlie Patton, with a full bag of stage tricks like playing guitar behind his back, and delighting the crowds by doing the splits and dancing around!

In the early 20’s the young Aaron Thibeaux (T-Bone) Walker seems to have shared the task of being Blind Lemon Jefferson’s lead-boy, helping him around Dallas, with Sam (Lightnin’) Hopkins doing the same job in Houston and Josh White taking him around Atlanta. Aaron was also keen on a career in the Blues, and he certainly imitated his step-father Marco Washington in playing any stringed instrument he could lay his hands on. Aaron travelled round Texas with various Carnivals and Medicine Shows, until 1929 when he was noticed by Columbia Records who put out ‘Wichita Falls Blues’ under the name Oak Cliff T-Bone. He won a talent contest in Dallas where the prize was to sing with Cab Calloway’s Big Band, and for the next four years, T-Bone played with a succession of swing bands around Texas. When he left for California in 1934, his place in Lawson Brooks’ Band was taken by his friend Charlie Christian, who would go on to electrify and revolutionise Jazz guitar in the same way T-Bone did with Blues guitar at the same time.

T-Bone plays that soulful guitar in a laid-back version of ‘Stormy Monday’.

In Los Angeles, T-Bone worked for several bands as a singer (and dancer!) notably fronting Les Hite’s Cotton Club Orchestra, but by the late 30’s he was experimenting with an electrified guitar. In 1939 he cut the seminal ‘T-Bone Blues’ and two years later he left Hite’s band to strike out on his own. In 1942 the newly-formed Capitol Records released ‘Mean Old World’ and suddenly the Blues took a big step forward. T-Bone’s elegant phrasing and fluent lead breaks signalled a paradigm shift for every guitar player from that day on.

In Chicago, the Rhumboogie Club provided a semi-residency for T-Bone, and he laid down a few tracks for the house label, but as WWII ended he went back to LA to sign for Black and White Records. Here he consolidated the style that became a template for BB King (plus Freddie and Albert), Buddy Guy, Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan. From the soulful ‘Stormy Monday’ to the rollicking ‘T-Bone Jumps Again’, he showed an assured mastery of the genre and sold truck loads of records.

In Chicago, the Rhumboogie Club provided a semi-residency for T-Bone, and he laid down a few tracks for the house label, but as WWII ended he went back to LA to sign for Black and White Records. Here he consolidated the style that became a template for BB King (plus Freddie and Albert), Buddy Guy, Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan. From the soulful ‘Stormy Monday’ to the rollicking ‘T-Bone Jumps Again’, he showed an assured mastery of the genre and sold truck loads of records.

The man had such style! Another TV appearance from the 60s;

T-Bone joined Imperial Records in 1950, and continued his prolific performance with tracks like ‘ Cold Cold Feeling’, ‘Blue Mood’ and ‘Party Girl’. After joining Atlantic he recorded in Chicago with Jimmy Rogers and Junior Wells, and in New Orleans with Dave Bartholemew and back in LA he cut astonishing instrumentals like ‘Two Bones and a Pick’ and ‘Blues Rock’.

Reluctant to take resposibility for leading a permanent band, T-Bone would tour The States picking up local backing musicians, confident that his own virtuosity would shine out from even an indifferent combo, despite the fact that his health was being undermined by his persistent alcoholism.