THE GREAT MIGRATION

It took a long time for The Blues to move from its rural heartlands to the big cities of America and from there out across the world, but it took that journey embedded in the memories and emotions of the people who loved the music. Fifty years after the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation, the vast majority of African-Americans still lived in rural poverty in the South. Freed slaves and black immigrants had been present in Northern cities like New York, Philadelphia and Chicago for a long time. After the 1860s their population grew there quickly, but they were not widespread in country areas, in the New Territories or on the West-coast.

It took a long time for The Blues to move from its rural heartlands to the big cities of America and from there out across the world, but it took that journey embedded in the memories and emotions of the people who loved the music. Fifty years after the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation, the vast majority of African-Americans still lived in rural poverty in the South. Freed slaves and black immigrants had been present in Northern cities like New York, Philadelphia and Chicago for a long time. After the 1860s their population grew there quickly, but they were not widespread in country areas, in the New Territories or on the West-coast.

Blues is heard across the South.

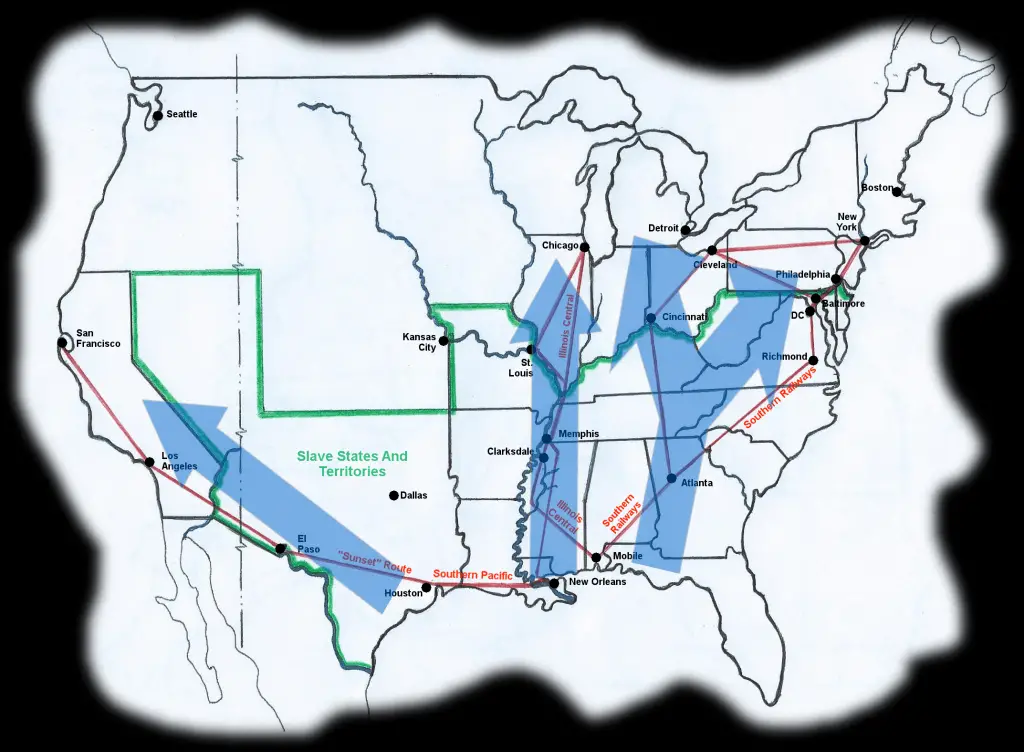

An early step in that momentous journey was back towards New Orleans, where in the last years of the 19th Century, Buddy Bolden and his cohorts were inventing the improvised music we know as Jazz, and they eagerly adopted the Blues form and scale as the basis for their extemporations. New Orleans had a long tradition of 'Free People of Color' stemming from its history as a French colony, and the music heard in Congo Square had deep African roots. 'Storyville', New Orleans' red-light-district where Jazz and Blues were heard in every bar and cat-house, was closed down by the Military during WW1, and musicians dispersed up the Mississippi to Memphis, St.Louis and onwards to the cities of the North, or round the eastern seaboard to the big urban areas of the North-East. By the end of WW1, the Blues had also spread all across the South, as singers and musicians in tent shows, vaudeville tours, medicine shows and circuses, as well as 'wandering songsters' on streetcorners and in juke-joints all used the 12-bar form in their songs.

The Great Migration was the term used to describe the movement of African-Americans from the South in search of better social and economic prospects. They relocated mainly to the northern cities after WW1, and again to the North but also to the West coast after WW2.

The Great War had caused a labour shortage as the economy accelerated under War conditions, while the supply of new immigrant workers from Europe was stopped dead. In 1917 the renowned Chicago newspaper The Defender called for 'The Great Northern Drive' to attract Southern blacks to better wages and more comfortable urban living conditions. This exodus was already underway to some extent as a result of the mechanisation of the cotton industry and the impact of boll-weevil infestation over the previous few years, and is known in Black History as The First Great Migration (the Second Migration covered the post-WWII period up to the Civil Rights Act). By the end of World War 1, Ku Klux Klan membership was running at 4million in the South and their violent persecution was commonplace, so fear was a motive in persuading some to migrate. All was not peaceful in the North either, with bloody Race Riots in several cities as the newcomers were often seen as strikebreakers who were also causing pressure on housing supply, but there was also a sense of security to be had in black neighborhoods.

Moving to the City.

Along with the people from the South, citizens of Chicago and New York also noticed a new kind of music on their streets: The Blues could be heard in bars and on streetcorners as musicians plied their trade for tips. When Mamie Smith's record of 'Crazy Blues' kick-started the 'race music' industry in 1920, record companies were quick to sign their own 'Blues Divas' and soon mobile recording units were bringing back the sound of country Blues to downtown 'speakeasies'. This led to the development of a more 'sophisticated' urban Blues by pioneers like Big Bill Broonzy and Tampa Red, with the 'band-sound' of producer Lester Melrose adding bass, drums and piano to the basic mix. When the economy recovered from 'The Crash of 29', a healthy live music scene and recording industry had been established in the cities, and the Blues had begun to change from a 'country' to an 'urban' music.

When the Second World War ended, the Second Great Migration began, again as a result of the pull of higher wages and better living conditions. The post-War economy was booming and the factories of the North could not get enough people onto their production lines to manufacture consumer goods. New opportunities on the West-coast led many Texans to take the 'Sunset Route'. Rapid progress seemed to be everywhere, and this was reflected in the music as Muddy Waters, BB King, John Lee Hooker and Little Walter were all Mississippi men who pioneered 'electric Chicago Blues', and their exciting, hard-edged music sounded like the future. Record sales were booming too, with juke-boxes and radio spreading the new sound far and wide, and before too long, the whole world had heard that rural folk music from the Mississippi Delta. The Jump-blues that had the whole country dancing was followed by the rollicking sax and piano-led music out of New Orleans and in another few years, "the Blues had a baby and they called it Rock'n'Roll".

When the British Beat Boom brought youthful, Blues-based sounds back to America in the 'British Invasion' of the 60s, the world of music would never be the same. This revolution occurred as a result of the music that people had carried with them in their hearts when they took part in The Great Migration. As BB King put it, “It all opened up then”.